Buck Conner1

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Oct 20, 2015

- Messages

- 4,592

- Reaction score

- 558

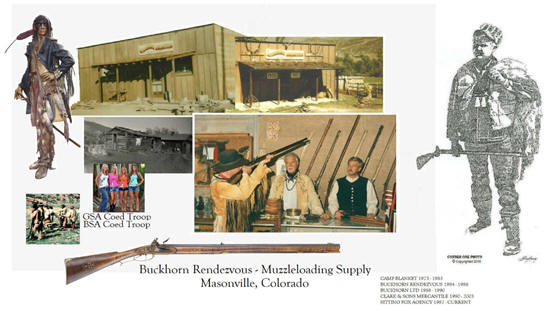

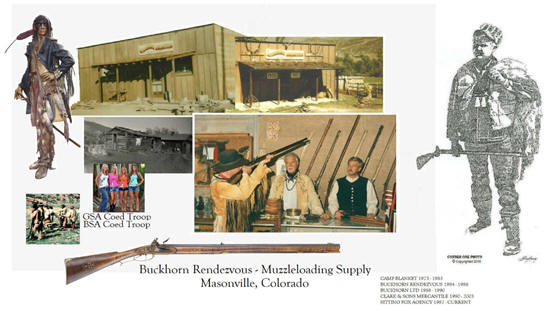

This information was assembled from several different sources for a group of Boy Scouts (BSA) and Girl Scouts (GSA) that wanted to be able to survive in the mountains. Out of nowhere we have mixed group of young folks (Boy Scouts) wanting to know about shooting muzzleloaders. We setup and hold a meeting one evening in my store Buckhorn Rendezvous, the meeting went well and it was decide to hold weekly Wed. evening meeting to get these young men on-board with their needs.

Apparently at school they told some friend and the following week we grew from 5 to 9 male members and 4 new drop-dead looking Girl Scouts that had heard about what we were doing. These girls ranged in age from 16 to 18, but looked like they were all in their early hot 20’s. Girls never ever looked like these kids when I went to school, those girls back then always had overweight problems and completion issues. I think that was why our male side of our group grew like it did. The girls wanted to know survival skills as they were all cross country skiers. This is touchy having boys and girls together, our friend Jim Seery (BSA Counselor) working out of the BSA Main Office contacted his group to see how this should be handled, being fair to both sides. He’s told that he would need the parent’s support 100% with them being involved per the Greeley BSA Council to protect those involved in this 1st mixed group of scouts in BSA or GSA history.

I can honestly say we enjoyed the time teaching them the skills of the mountain men, having them read the history of these folks, making all their personal equipage from clothing, foot ware to forged fire irons, strikers, and their own belt and patch knives. Required to read at least two of a dozen books suggested on the subject. The parents purchased CVA kit rifles and helped assemble them in my shop (us as tech guides) for Christmas presents that our kids knew nothing about. CVA provided this group kit rifles at dist. cost along with giving each new shooter involved a free starter kit to shoot their rifles saving the families money for other items needed. Buckhorn Rendezvous provided a can of Goex black powder and a box of Hornady swaged balls. What really surprised Jim Seery (retired Navy Nurse, BSA Counselor and blacksmith – furnished his forge and acted as instructor), Ben Thompson (a retired Seal from Seal Team One) my employee and a history nut) and myself (store owner and historian nut). We found very quickly the girls were better at each skill set we provided them (making things to shooting). The boys thought they knew more than we did and didn’t pay attention like the young ladies did.

Our Project Objective was to have each member (boys and girls) fully equipped that they would fit in any sizeable rendezvous and “shine”, plus have gained the knowledge (history of the North American Fur Trade) and have those original skills to survive if need be in the mountains being hikers and cross country ski fans. The BSA/GSA Councils from Greeley used pictures of the group with their parents at different events for several years in each groups advertising.

CVA wrote asking permission to use pictures and tell the story of these young men and women’s. CVA’s write up was used at different events when promoting their products (these kids were super stars in the area with Denver papers repeating what had been done in one year).

CVA wrote asking permission to use pictures and tell the story of these young men and women’s. CVA’s write up was used at different events when promoting their products (these kids were super stars in the area with Denver papers repeating what had been done in one year).

HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN FUR TRADE

It was the search for the famed “Northwest Passage” which revealed America as a source for the fur-bearing beaver. The Northwest Passage, which would have provided a faster and more direct route to the Far East, was, of course, never found as it does not exist. What was found, however, was an over-abundance of beaver in the lakes, streams and rivers of the North American continent. As beaver were extinct in Europe, this was a magnificent find. Beavers were highly desired for their fur which was utilized to manufacture the fashionable hats of the period. The first to discover this great wealth were the French of 17th and 18th century Canada. However in 1763, Britain’s victory over France in the French and Indian War revealed a new leader of the American fur trade, and the Hudson’s Bay Company along with independent trappers monopolized the business for the next two decades. By 1787, the independent trappers formed a coalition under the name of the North West Company and challenged the supremacy of the Hudson’s Bay Company, rivaling for the rights to establish forts in what is now west-central Canada and on the Pacific Coast.

Inevitably, the clashing of interests led to arguments, bribery, thievery, arson and even murder. The rivalries between the companies knew no bounds. When London got hold of the scandal in 1821, the British government forced the two competitors to unite as an enlarged business under the single name of the Hudson’s Bay Company. With the two forces joined, their tactics were now turned to eliminating the opposition, the American Fur Company, which had been secured by a charter from the state of New York on April 6, 1808. To further complicate matters, the Russians had also found an interest in the Pacific Coast where sea otter were in abundance. The Russians were transporting furs to the Siberian coast where they were then shipped to China. One of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s first major moves was the establishment of Fort Vancouver at the mouth of the Willamette River in Oregon Country. The new manager of the joined company, George Simpson, encouraged his men to range as far west and as far south as possible and to trap the beavers to extinction. This would in turn create a “buffer zone” or “fur desert” that would be worthless to American fur trappers. As Britain and the United States had agreed by treaty to share the occupation of this territory, this blatant attempt at monopolization ignited American tempers.

Meanwhile, the Hudson’s Bay Company had discovered a new and competent rival in John Jacob Astor who’s American Fur Company by 1810 was already a dominant force in the region of the Great Lakes. Astor was a commercial genius; a German immigrant who had landed at Baltimore in the spring of 1784 to seek his fortune. He traded the small assortment of musical instruments he had brought with him from Germany for beaver pelts which he sold to London for profit. His modest beginnings soon developed into the start of a small fortune and by 1800 Astor had become a powerful man of the trade. With his American Fur Company already an established success, Astor attempted to attain a monopoly of the entire region with the creation of the Pacific Fur Company on June 23, 1810 as a subsidiary of his present company. Astor planned to build a large post, Astoria, at the mouth of the Columbia River in Oregon Country as a direct rival to the still existing North West Company. In September of 1810, the Tonquin was dispatched from New York under the command of Captain Jonathan Thorp to sail around Cape Horn and on to Astoria.

The Tonquin had barely set sail when dissention started between Captain Thorp and the ship’s passengers, four of Astor’s partners and twenty-nine employees of the company. Finally, after a stormy seven-month journey, the Tonquin reached land and with the small party that remained began construction of Fort Astoria on the southern bank of the Columbia.

Soon after their arrival, the Tonquin began trading with the coastal Indian tribes. All went well until in anger, Captain Thorp slapped a Chinook chief across the face. The avenging Indians countered with an attack on the Tonquin, killing all but five of the men aboard. Four of these men were later captured and tortured to death and the fifth, again escaping detection, blew himself and the ship to pieces the following day as the Indians returned for a final looting of the ship.

At the same time the Tonquin was dispatched, a second expedition was preparing to journey overland to Astoria. The party of overland Astorians left St. Louis in early 1811 under command of Wilson Price Hunt, following the trail that Lewis and Clark had earlier used. Detours from this trail were taken, however, to avoid attack by the Blackfoot Indians. The party followed the Snake River in canoes. When the river became unnavigable, the party separated into smaller groups and traveled by foot, reaching Astoria in the winter of 1812 in very poor condition. By the following June, the War of 1812 had broken out between Britain and the United States. The Astorians had little choice but to sell their fort and all its equipment, stores and outposts to the North West Company in 1813. The first United States attempt at establishing control of Oregon Country had failed to realize Astor’s ambition. However, the attempt later played an important role in the treaties of 1818 and 1828 with Britain in which the two nations agreed to share control of Oregon Country; and, later, in the negotiations that recognized Oregon as part of the United States.

Prior to Astor’s venture to the Pacific Coast, other Americans had been trapping in the Rocky Mountain region of the United States. With the return of the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1806 other Americans began to develop a fever for the fur-bearing creature. As Lewis and Clark were about to start the final leg of their journey from the mouth of the Yellowstone River, they met two American trappers heading West to the Rockies. John Colter was asked to accompany the trappers as a guide and, with the permission of the Captains, spent the fall and winter trapping beaver on the Yellowstone. Tiring of the mountains, Colter started his return trip to St. Louis down the Missouri alone. At the mouth of the Platte River in the spring of 1807, he met a new brigade of trappers commanded by Manuel Lisa, one of the most successful fur traders of St. Louis, and was once again persuaded to return west. Colter returned at the end of the season with a wealth of pelts which Lisa brought to St. Louis for trading. This success enabled Lisa to form the St. Louis Missouri Fur Company whose first brigade of trappers was sent upriver in 1809. However, the party returned in failure in July of 1811 and therein led to the Company’s downfall. Between 1812 and Lisa’s death in 1820, the Missouri Fur Company underwent several reorganizations. With the loss of Lisa and thus the company’s driving inspirational force, the Missouri Fur Company lasted only until June of 1830.

After a lull in the fur trade caused by economic and political repercussions of the War of 1812, the American fur trade once again revived in the 1820s. William Henry Ashley and Andrew Henry, a former partner of Lisa’s, began the establishment of the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade Company by placing an advertisement in St. Louis newspapers in 1822. The ad read simply: “To enterprising young men. The subscriber wishes to engage one-hundred young men to ascent Missouri river to its source, there to be employed for one, two, or three years.” The expedition left St. Louis around April 15th of that year with men such as Jim Bridger, William and Milton Sublette, Hugh Glass, Thomas Fitzpatrick, Jim Beckwourth and Jedediah Strong Smith. The men traveled up the Missouri River by boat to establish a fort and trading post. Trouble arose with the Arikara Indians and Ashley decided to abort the river expedition due to the impending dangers. Instead, he would send his men overland in small groups with a year’s provisions “on credit” in return for the year’s pelts, which would be exchanged at a predesignated meeting place in the mountains. The men would trap on their own rather than trading American goods with the Indians for pelts, as had previously been the arrangement. Rather than having the men spend considerable time to travel to St. Louis, Ashley would bring the supplies to the trappers. Thus was born the tradition of the Rocky Mountain Rendezvous and the free trapper who bore the name of the “mountain man.”

Henry retired in 1824 while Ashley continued to journey to the yearly rendezvous through 1826 when he left the mountain life to pursue a political career. On July 18, 1826, the articles of agreement were signed and the company passed to the hands of Jedediah Smith, David Jackson and William Sublette with the newly formed name of Smith, Jackson and Sublette. In 1830, Smith and his associates sold their company to Thomas Fitzpatrick, Jim Bridger, Milton Sublette, Robert Campbell and Henry Fraeb. The final downfall of the company was marked by the rendezvous in the Green River valley during the summer of 1834 when, amid many discouraging conditions, Campbell and Fraeb sold their interests in the partnership the following fall. The company continued under the control of Fitzpatrick, Bridger and Sublette who sold the company to the American Fur Company the following year.

The year 1824 marked a tremendous increase in the number and activity of those entering the business of the fur trade. American trappers had now begun to penetrate the southern and central Rockies from new bases at Taos and Santa Fe, rivaling the well organized and established base at St. Louis. About April 1, 1824, the first Santa Fe expedition was organized in Franklin, Missouri. After a successful expedition, the party returned home to Franklin on September 24, 1824. American fur traders had been drawn to this region after the independence of Mexico from Spain and during the next decade the fur trade and the Santa Fe trade had developed in direct proportion with each other, constituting a primary portion of the overland commerce to Missouri.

But America’s greed for the fur-bearing beaver had all but depleted its supply and, coupled with lower prices for pelts and the new trend towards Chinese silk in European fashions and coonskin caps in Poland, Russia and Germany, the fur trade began its rapid decline. With the sale of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company in 1834, the American Fur Company had achieved a monopoly. However, Astor, foreseeing the inevitable end of the fur trade, sold his shares to the company before the deal had been completed. By the mid-1830s the beaver trade was doomed. By the 1840s, the beaver trade was finished. Trading activity passed from the rendezvous site to key trading posts like Fort Laramie, Fort Bridger and Bent’s Fort.

For several trappers the end of the beaver trade was the beginning of fame, if not fortune, as guides for emigrant wagon trains traveling west to Oregon and California. Some guided the U.S. Army on exploratory expeditions into the Rocky Mountains. Others will become famous army scouts fighting the Indians, who were once their partners in the beaver trade.

Though their days of glory lasted little more than twenty years, these rugged individuals left a permanent mark on the history and legend of the west.

MOUNTAIN MEN OF WYOMING

It is a documented fact that John Colter, after leaving the Lewis and Clark expedition to travel with Manuel Lisa, traveled through Pryor Gap and passed through the present city of Cody and Yellowstone Park. Some believe that he wintered in Pierre’s Hole on the Idaho side of the Tetons; however, the only evidence of his stay is a much disputed rock measuring 4x8x13 inches and bearing the profile and name “John Colter” and the date “1808.”

The overland Astorians on their journey to Fort Astoria entered northeastern Wyoming near the Big Horn Mountains in late summer of 1811. That fall, the party observed the magnificent Tetons before following the Columbia River to Astoria, arriving in January, 1812.

On October 21, 1812, Robert Stuart led a party of returning Astorians through South Pass on their return to St. Louis, bringing news to Astor’s agents about the loss of the Tonquin and her crew. The path he followed would one day become the famous Oregon Trail that led thousands of emigrants to their new homes in the Pacific Northwest. It should be noted, however, that some historians believe South Pass was discovered by Andrew Henry in 1811. Still others argue that the Pass was not found until later by Etienne Provost, Thomas Fitzpatrick and Jedediah Smith. Credit, none the less, is given to Robert Stuart for the discovery of South Pass.

Ten days following Stuart’s discovery of South Pass, he and his party happened upon a striking fall of water which he named the “Fiery Narrows.” This landmark is today located off highway 220 near Alcova, thirty miles west of Casper. At Bessemer Bend, Stuart’s party built the first cabin in Wyoming, planning to spend the winter. Due to hostile Indians, however, the party relocated near present-day Torrington, establishing a second camp on New Year’s Day. On March 20th the party broke camp and followed the Platte to the Missouri, arriving in St. Louis on April 30, 1813.

In 1820, a fur trapper named LaRamee told companions that he was heading up a tributary of the Platte River to trap beaver. He planned to return the following spring and when he did not appear, his friends became worried and sent out a search party. He was found dead in a cabin about twenty-three days from the mouth of the river.

Years later in 1868, Jim Bridger told John Hunton, an old time resident of Fort Laramie, that while in his teens, he had been a participant of the search party which had been sent to find LaRamee. Bridger claimed that the party found an unfinished cottonwood cabin and one broken beaver trap but no LaRamee. Two years following the search, the Arapahoes had told Bridger that they had killed LaRamee and placed his body under the ice in a beaver dam. Nevertheless, the name of LaRamee lives on in its corrupted American version, Laramie. His name was left to the Laramie River, Laramie Peak, Laramie Plains, Laramie County, Fort Laramie, the town of Fort Laramie, and the city of Laramie, Wyoming.

It is interesting to note that Fort Laramie began as a fur trading post named Fort William, after William Sublette. In 1834, Sublette and Robert Cambell joined forces against the all-powerful American Fur Company and built Fort William on the Laramie River, more commonly called Fort Laramie. In the fall of 1834, the fort was sold to Jim Bridger, Thomas Fitzpatrick and Milton Sublette, who subsequently sold the fort to the American Fur Company the following year. In 1841, the American Fur company rebuilt the fort buildings, replacing the log with adobe, and renamed the post Fort John. With the decline of the fur trade, the fort began to take on military significance as a supply post due to its strategic western location. By the 1860s and 1870s, Fort Laramie had become the most important post on the Northern Plains, serving as a Pony Express and Overland Stage Station, an army base, and a supply center and protective shelter for ranchers and homesteaders.

The fort was abandoned in 1890 and lay idle until 1937 when the State of Wyoming bought 214 acres for the creation of Fort Laramie National Historic Site in 1938.

In April of 1830, William Sublette set out from St. Louis for the Wind River Rendezvous, determined to see if the trek from St. Louis to the West could be made by wagon. On July 4th, Sublette stopped at Independence Rock on the Sweetwater River and possibly gave the rock its name.

Following closely behind Sublette, Captain Benjamin Louis Eulalie de Bonneville, a Frenchman by birth and a graduate of West Point, entered the fur trade upon a two-year leave of absence from the army. Financially backed, Bonneville’s outfit of 110 men with goods and supplies left Independence, Missouri in twenty wagons. Bonneville’s wagons went by way of South Pass, over the Continental Divide and to the west of the Wind River Range. On the Green River in western Wyoming, Bonneville constructed a post which trappers graciously nicknamed “Fort Nonsense” and “Bonneville’s Folly.” Due to competition from numerous fur enterprises in the region and bad business practices Bonneville, at the end of three years, was bankrupt.

There has been much debate as to the mission of Captain Bonneville. Many attest to the belief that he was not simply in the region to reap a profit, but rather as an agent of the United States government, to report on the activities of the British in Oregon Country. There has never been any positive evidence produced in support of this position.

Beginning in 1843 Jim Bridger built Fort Bridger, on Blacks Fork of the Green River. Like Fort Laramie, Fort Bridger enabled the mountain men to get supplies year round when they needed them and not have to wait until the next summer’s rendezvous. Later, Fort Bridger will become important as a supply stop-over on the Oregon Trail for pioneers. In 1858 the United States Army rebuilt the trading post as a permanent military post that remained active until 1890.

It is William Ashley’s rendezvous, however, for which Wyoming is most famous. Except for two locations in Northern Utah and Pierre’s Hole on the Idaho side of the Tetons, all summer rendezvous were held at various sites in Wyoming. The first was held in 1825 on Henry’s Fork near present day McKinnon in the southwest corner of the state. Two rendezvous were held on the Popo Agie River near Lander, one on Ham’s Fork near Granger and six were held on the Green River, including the last two rendezvous of 1839 and 1840. With its strategic location in the northern Rockies and its abundance of beaver-rich rivers and streams, Wyoming became a true participant in the American fur trade.

THE BEAVER

It was not the fur of the beaver which made him one of the most sought after animals in Europe and North America, but rather the pelt for its barbed, fibrous under hair which was pounded, mashed, stiffened, and rolled to make felting material for hats. Hats of all descriptions were produced from this highly valued hair. Coats of a light coloring were used to make day-time hats and those of a more luxurious dark brown produced the elegant hats of the evening. Many shapes and styles were created to satisfy the fashion demand, formal and informal styles and even some military headgear were made of beaver. From the 17th century through the mid-19th century, no European was without a beaver hat. Then the styles turned to other fabrics such as Oriental silk, and the beaver hat was locked away in the closet.

The beaver is an amphibious creature which averages four feet long from the tip of the nose to the end of the tail. Weighing about forty pounds, the beaver is the second largest rodent in the world. The tail, which is noted for its flat, rounded appearance, is ten to fifteen inches in length and covered with rough skin that resembles scales. The tail allows the beaver to steer in water and signal other beavers by slapping the water. The beaver is an excellent swimmer, and while under water can seal its ears, mouth, and nostrils. The beaver is generally light brown in color, although some may possess very dark coats. Their teeth are much longer and more powerful than those of most other animals and are used to fell trees which constitute the basis of their vegetarian diet, especially the bark of the birch, willow and cottonwood trees. Aspen trees are the favorite food of the beaver. The beaver uses its front feet to grasp trees and the webbed hind feet to swim. The beaver can cut trees down in a matter of minutes and is considered one of the finest engineers in the world in building dams. The beaver often emits a small quantity of castoreum (castor) upon the river bank, which will attract every beaver in the area. The odorous substance is used to “mark territory.” Trappers took advantage of this process and collected the castoreum left upon the banks, replacing the substance strategically above the traps. The beaver would be lured by the odor and then caught by the traps which lay beneath the surface of the water.

According to legend, the Indian tribes of early America respected and often worshipped the beaver. The Algonquin tribes along the St. Lawrence River believed that thunder was produced by their almighty beaver father, Quahbeet, as he slapped his giant tail against the ground. The five nations of the Iroquois confederacy were bound together by their common clans, such as the “beaver clan” in which members of the tribe were reincarnated as beavers. In this way, any beaver in the vicinity of the tribe could be a close friend or relative. Many tribes shared this belief, thereby they refused to hunt beaver near their homelands as they might be killing a loved one. The Flathead tribe thought that beavers were a race of man that had angered the Great Spirit and, as punishment, were sentenced to a life of hard labor. In time the Indians’ adherence to the legends, however, was treated more casually with the introduction of the white man’s materials. The tribes valued the beaver pelts only as winter clothing and as bed robes; therefore, they were quite willing to trade these pelts for the much coveted modern articles from the States.

TIMELINE

1743 - Verendryes brothers, first Europeans to enter Wyoming

1803 - Louisiana Purchase

1806 - John Colter first white American to enter Wyoming

1811 - Wilson Price Hunt’s party crosses Wyoming

1812 - Robert Stuart’s party returning from Oregon discovers South Pass

1823 - William Ashley’s fur trappers arrive in Wyoming led by Jedediah Smith

1824 - Ashley’s trappers cross South Pass westward and find good trapping on the Green River and its tributaries

1825 - First rendezvous held in Wyoming on Henry’s Fork of the Green River 1826 - First recorded visit to Yellowstone Park by trappers

1826 - Ashley sells out to Jed Smith, D. Sublette, W. Sublette

1830 - First wagons being drawn by mules cross Wyoming to rendezvous

1830 - Rocky Mountain Fur Company organized

1832 - Battle of Pierre’s Hole

1832 - Captain Bonneville takes first wagons over South Pass

1834 - Fort William built (later Fort John and finally Fort Laramie)

1840 - Last rendezvous held

1842 - Fort Bridger established

Apparently at school they told some friend and the following week we grew from 5 to 9 male members and 4 new drop-dead looking Girl Scouts that had heard about what we were doing. These girls ranged in age from 16 to 18, but looked like they were all in their early hot 20’s. Girls never ever looked like these kids when I went to school, those girls back then always had overweight problems and completion issues. I think that was why our male side of our group grew like it did. The girls wanted to know survival skills as they were all cross country skiers. This is touchy having boys and girls together, our friend Jim Seery (BSA Counselor) working out of the BSA Main Office contacted his group to see how this should be handled, being fair to both sides. He’s told that he would need the parent’s support 100% with them being involved per the Greeley BSA Council to protect those involved in this 1st mixed group of scouts in BSA or GSA history.

I can honestly say we enjoyed the time teaching them the skills of the mountain men, having them read the history of these folks, making all their personal equipage from clothing, foot ware to forged fire irons, strikers, and their own belt and patch knives. Required to read at least two of a dozen books suggested on the subject. The parents purchased CVA kit rifles and helped assemble them in my shop (us as tech guides) for Christmas presents that our kids knew nothing about. CVA provided this group kit rifles at dist. cost along with giving each new shooter involved a free starter kit to shoot their rifles saving the families money for other items needed. Buckhorn Rendezvous provided a can of Goex black powder and a box of Hornady swaged balls. What really surprised Jim Seery (retired Navy Nurse, BSA Counselor and blacksmith – furnished his forge and acted as instructor), Ben Thompson (a retired Seal from Seal Team One) my employee and a history nut) and myself (store owner and historian nut). We found very quickly the girls were better at each skill set we provided them (making things to shooting). The boys thought they knew more than we did and didn’t pay attention like the young ladies did.

Our Project Objective was to have each member (boys and girls) fully equipped that they would fit in any sizeable rendezvous and “shine”, plus have gained the knowledge (history of the North American Fur Trade) and have those original skills to survive if need be in the mountains being hikers and cross country ski fans. The BSA/GSA Councils from Greeley used pictures of the group with their parents at different events for several years in each groups advertising.

June 10, 1986

Required Reading.HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN FUR TRADE

It was the search for the famed “Northwest Passage” which revealed America as a source for the fur-bearing beaver. The Northwest Passage, which would have provided a faster and more direct route to the Far East, was, of course, never found as it does not exist. What was found, however, was an over-abundance of beaver in the lakes, streams and rivers of the North American continent. As beaver were extinct in Europe, this was a magnificent find. Beavers were highly desired for their fur which was utilized to manufacture the fashionable hats of the period. The first to discover this great wealth were the French of 17th and 18th century Canada. However in 1763, Britain’s victory over France in the French and Indian War revealed a new leader of the American fur trade, and the Hudson’s Bay Company along with independent trappers monopolized the business for the next two decades. By 1787, the independent trappers formed a coalition under the name of the North West Company and challenged the supremacy of the Hudson’s Bay Company, rivaling for the rights to establish forts in what is now west-central Canada and on the Pacific Coast.

Inevitably, the clashing of interests led to arguments, bribery, thievery, arson and even murder. The rivalries between the companies knew no bounds. When London got hold of the scandal in 1821, the British government forced the two competitors to unite as an enlarged business under the single name of the Hudson’s Bay Company. With the two forces joined, their tactics were now turned to eliminating the opposition, the American Fur Company, which had been secured by a charter from the state of New York on April 6, 1808. To further complicate matters, the Russians had also found an interest in the Pacific Coast where sea otter were in abundance. The Russians were transporting furs to the Siberian coast where they were then shipped to China. One of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s first major moves was the establishment of Fort Vancouver at the mouth of the Willamette River in Oregon Country. The new manager of the joined company, George Simpson, encouraged his men to range as far west and as far south as possible and to trap the beavers to extinction. This would in turn create a “buffer zone” or “fur desert” that would be worthless to American fur trappers. As Britain and the United States had agreed by treaty to share the occupation of this territory, this blatant attempt at monopolization ignited American tempers.

Meanwhile, the Hudson’s Bay Company had discovered a new and competent rival in John Jacob Astor who’s American Fur Company by 1810 was already a dominant force in the region of the Great Lakes. Astor was a commercial genius; a German immigrant who had landed at Baltimore in the spring of 1784 to seek his fortune. He traded the small assortment of musical instruments he had brought with him from Germany for beaver pelts which he sold to London for profit. His modest beginnings soon developed into the start of a small fortune and by 1800 Astor had become a powerful man of the trade. With his American Fur Company already an established success, Astor attempted to attain a monopoly of the entire region with the creation of the Pacific Fur Company on June 23, 1810 as a subsidiary of his present company. Astor planned to build a large post, Astoria, at the mouth of the Columbia River in Oregon Country as a direct rival to the still existing North West Company. In September of 1810, the Tonquin was dispatched from New York under the command of Captain Jonathan Thorp to sail around Cape Horn and on to Astoria.

The Tonquin had barely set sail when dissention started between Captain Thorp and the ship’s passengers, four of Astor’s partners and twenty-nine employees of the company. Finally, after a stormy seven-month journey, the Tonquin reached land and with the small party that remained began construction of Fort Astoria on the southern bank of the Columbia.

Soon after their arrival, the Tonquin began trading with the coastal Indian tribes. All went well until in anger, Captain Thorp slapped a Chinook chief across the face. The avenging Indians countered with an attack on the Tonquin, killing all but five of the men aboard. Four of these men were later captured and tortured to death and the fifth, again escaping detection, blew himself and the ship to pieces the following day as the Indians returned for a final looting of the ship.

At the same time the Tonquin was dispatched, a second expedition was preparing to journey overland to Astoria. The party of overland Astorians left St. Louis in early 1811 under command of Wilson Price Hunt, following the trail that Lewis and Clark had earlier used. Detours from this trail were taken, however, to avoid attack by the Blackfoot Indians. The party followed the Snake River in canoes. When the river became unnavigable, the party separated into smaller groups and traveled by foot, reaching Astoria in the winter of 1812 in very poor condition. By the following June, the War of 1812 had broken out between Britain and the United States. The Astorians had little choice but to sell their fort and all its equipment, stores and outposts to the North West Company in 1813. The first United States attempt at establishing control of Oregon Country had failed to realize Astor’s ambition. However, the attempt later played an important role in the treaties of 1818 and 1828 with Britain in which the two nations agreed to share control of Oregon Country; and, later, in the negotiations that recognized Oregon as part of the United States.

Prior to Astor’s venture to the Pacific Coast, other Americans had been trapping in the Rocky Mountain region of the United States. With the return of the Lewis and Clark Expedition in 1806 other Americans began to develop a fever for the fur-bearing creature. As Lewis and Clark were about to start the final leg of their journey from the mouth of the Yellowstone River, they met two American trappers heading West to the Rockies. John Colter was asked to accompany the trappers as a guide and, with the permission of the Captains, spent the fall and winter trapping beaver on the Yellowstone. Tiring of the mountains, Colter started his return trip to St. Louis down the Missouri alone. At the mouth of the Platte River in the spring of 1807, he met a new brigade of trappers commanded by Manuel Lisa, one of the most successful fur traders of St. Louis, and was once again persuaded to return west. Colter returned at the end of the season with a wealth of pelts which Lisa brought to St. Louis for trading. This success enabled Lisa to form the St. Louis Missouri Fur Company whose first brigade of trappers was sent upriver in 1809. However, the party returned in failure in July of 1811 and therein led to the Company’s downfall. Between 1812 and Lisa’s death in 1820, the Missouri Fur Company underwent several reorganizations. With the loss of Lisa and thus the company’s driving inspirational force, the Missouri Fur Company lasted only until June of 1830.

After a lull in the fur trade caused by economic and political repercussions of the War of 1812, the American fur trade once again revived in the 1820s. William Henry Ashley and Andrew Henry, a former partner of Lisa’s, began the establishment of the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade Company by placing an advertisement in St. Louis newspapers in 1822. The ad read simply: “To enterprising young men. The subscriber wishes to engage one-hundred young men to ascent Missouri river to its source, there to be employed for one, two, or three years.” The expedition left St. Louis around April 15th of that year with men such as Jim Bridger, William and Milton Sublette, Hugh Glass, Thomas Fitzpatrick, Jim Beckwourth and Jedediah Strong Smith. The men traveled up the Missouri River by boat to establish a fort and trading post. Trouble arose with the Arikara Indians and Ashley decided to abort the river expedition due to the impending dangers. Instead, he would send his men overland in small groups with a year’s provisions “on credit” in return for the year’s pelts, which would be exchanged at a predesignated meeting place in the mountains. The men would trap on their own rather than trading American goods with the Indians for pelts, as had previously been the arrangement. Rather than having the men spend considerable time to travel to St. Louis, Ashley would bring the supplies to the trappers. Thus was born the tradition of the Rocky Mountain Rendezvous and the free trapper who bore the name of the “mountain man.”

Henry retired in 1824 while Ashley continued to journey to the yearly rendezvous through 1826 when he left the mountain life to pursue a political career. On July 18, 1826, the articles of agreement were signed and the company passed to the hands of Jedediah Smith, David Jackson and William Sublette with the newly formed name of Smith, Jackson and Sublette. In 1830, Smith and his associates sold their company to Thomas Fitzpatrick, Jim Bridger, Milton Sublette, Robert Campbell and Henry Fraeb. The final downfall of the company was marked by the rendezvous in the Green River valley during the summer of 1834 when, amid many discouraging conditions, Campbell and Fraeb sold their interests in the partnership the following fall. The company continued under the control of Fitzpatrick, Bridger and Sublette who sold the company to the American Fur Company the following year.

The year 1824 marked a tremendous increase in the number and activity of those entering the business of the fur trade. American trappers had now begun to penetrate the southern and central Rockies from new bases at Taos and Santa Fe, rivaling the well organized and established base at St. Louis. About April 1, 1824, the first Santa Fe expedition was organized in Franklin, Missouri. After a successful expedition, the party returned home to Franklin on September 24, 1824. American fur traders had been drawn to this region after the independence of Mexico from Spain and during the next decade the fur trade and the Santa Fe trade had developed in direct proportion with each other, constituting a primary portion of the overland commerce to Missouri.

But America’s greed for the fur-bearing beaver had all but depleted its supply and, coupled with lower prices for pelts and the new trend towards Chinese silk in European fashions and coonskin caps in Poland, Russia and Germany, the fur trade began its rapid decline. With the sale of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company in 1834, the American Fur Company had achieved a monopoly. However, Astor, foreseeing the inevitable end of the fur trade, sold his shares to the company before the deal had been completed. By the mid-1830s the beaver trade was doomed. By the 1840s, the beaver trade was finished. Trading activity passed from the rendezvous site to key trading posts like Fort Laramie, Fort Bridger and Bent’s Fort.

For several trappers the end of the beaver trade was the beginning of fame, if not fortune, as guides for emigrant wagon trains traveling west to Oregon and California. Some guided the U.S. Army on exploratory expeditions into the Rocky Mountains. Others will become famous army scouts fighting the Indians, who were once their partners in the beaver trade.

Though their days of glory lasted little more than twenty years, these rugged individuals left a permanent mark on the history and legend of the west.

MOUNTAIN MEN OF WYOMING

It is a documented fact that John Colter, after leaving the Lewis and Clark expedition to travel with Manuel Lisa, traveled through Pryor Gap and passed through the present city of Cody and Yellowstone Park. Some believe that he wintered in Pierre’s Hole on the Idaho side of the Tetons; however, the only evidence of his stay is a much disputed rock measuring 4x8x13 inches and bearing the profile and name “John Colter” and the date “1808.”

The overland Astorians on their journey to Fort Astoria entered northeastern Wyoming near the Big Horn Mountains in late summer of 1811. That fall, the party observed the magnificent Tetons before following the Columbia River to Astoria, arriving in January, 1812.

On October 21, 1812, Robert Stuart led a party of returning Astorians through South Pass on their return to St. Louis, bringing news to Astor’s agents about the loss of the Tonquin and her crew. The path he followed would one day become the famous Oregon Trail that led thousands of emigrants to their new homes in the Pacific Northwest. It should be noted, however, that some historians believe South Pass was discovered by Andrew Henry in 1811. Still others argue that the Pass was not found until later by Etienne Provost, Thomas Fitzpatrick and Jedediah Smith. Credit, none the less, is given to Robert Stuart for the discovery of South Pass.

Ten days following Stuart’s discovery of South Pass, he and his party happened upon a striking fall of water which he named the “Fiery Narrows.” This landmark is today located off highway 220 near Alcova, thirty miles west of Casper. At Bessemer Bend, Stuart’s party built the first cabin in Wyoming, planning to spend the winter. Due to hostile Indians, however, the party relocated near present-day Torrington, establishing a second camp on New Year’s Day. On March 20th the party broke camp and followed the Platte to the Missouri, arriving in St. Louis on April 30, 1813.

In 1820, a fur trapper named LaRamee told companions that he was heading up a tributary of the Platte River to trap beaver. He planned to return the following spring and when he did not appear, his friends became worried and sent out a search party. He was found dead in a cabin about twenty-three days from the mouth of the river.

Years later in 1868, Jim Bridger told John Hunton, an old time resident of Fort Laramie, that while in his teens, he had been a participant of the search party which had been sent to find LaRamee. Bridger claimed that the party found an unfinished cottonwood cabin and one broken beaver trap but no LaRamee. Two years following the search, the Arapahoes had told Bridger that they had killed LaRamee and placed his body under the ice in a beaver dam. Nevertheless, the name of LaRamee lives on in its corrupted American version, Laramie. His name was left to the Laramie River, Laramie Peak, Laramie Plains, Laramie County, Fort Laramie, the town of Fort Laramie, and the city of Laramie, Wyoming.

It is interesting to note that Fort Laramie began as a fur trading post named Fort William, after William Sublette. In 1834, Sublette and Robert Cambell joined forces against the all-powerful American Fur Company and built Fort William on the Laramie River, more commonly called Fort Laramie. In the fall of 1834, the fort was sold to Jim Bridger, Thomas Fitzpatrick and Milton Sublette, who subsequently sold the fort to the American Fur Company the following year. In 1841, the American Fur company rebuilt the fort buildings, replacing the log with adobe, and renamed the post Fort John. With the decline of the fur trade, the fort began to take on military significance as a supply post due to its strategic western location. By the 1860s and 1870s, Fort Laramie had become the most important post on the Northern Plains, serving as a Pony Express and Overland Stage Station, an army base, and a supply center and protective shelter for ranchers and homesteaders.

The fort was abandoned in 1890 and lay idle until 1937 when the State of Wyoming bought 214 acres for the creation of Fort Laramie National Historic Site in 1938.

In April of 1830, William Sublette set out from St. Louis for the Wind River Rendezvous, determined to see if the trek from St. Louis to the West could be made by wagon. On July 4th, Sublette stopped at Independence Rock on the Sweetwater River and possibly gave the rock its name.

Following closely behind Sublette, Captain Benjamin Louis Eulalie de Bonneville, a Frenchman by birth and a graduate of West Point, entered the fur trade upon a two-year leave of absence from the army. Financially backed, Bonneville’s outfit of 110 men with goods and supplies left Independence, Missouri in twenty wagons. Bonneville’s wagons went by way of South Pass, over the Continental Divide and to the west of the Wind River Range. On the Green River in western Wyoming, Bonneville constructed a post which trappers graciously nicknamed “Fort Nonsense” and “Bonneville’s Folly.” Due to competition from numerous fur enterprises in the region and bad business practices Bonneville, at the end of three years, was bankrupt.

There has been much debate as to the mission of Captain Bonneville. Many attest to the belief that he was not simply in the region to reap a profit, but rather as an agent of the United States government, to report on the activities of the British in Oregon Country. There has never been any positive evidence produced in support of this position.

Beginning in 1843 Jim Bridger built Fort Bridger, on Blacks Fork of the Green River. Like Fort Laramie, Fort Bridger enabled the mountain men to get supplies year round when they needed them and not have to wait until the next summer’s rendezvous. Later, Fort Bridger will become important as a supply stop-over on the Oregon Trail for pioneers. In 1858 the United States Army rebuilt the trading post as a permanent military post that remained active until 1890.

It is William Ashley’s rendezvous, however, for which Wyoming is most famous. Except for two locations in Northern Utah and Pierre’s Hole on the Idaho side of the Tetons, all summer rendezvous were held at various sites in Wyoming. The first was held in 1825 on Henry’s Fork near present day McKinnon in the southwest corner of the state. Two rendezvous were held on the Popo Agie River near Lander, one on Ham’s Fork near Granger and six were held on the Green River, including the last two rendezvous of 1839 and 1840. With its strategic location in the northern Rockies and its abundance of beaver-rich rivers and streams, Wyoming became a true participant in the American fur trade.

THE BEAVER

It was not the fur of the beaver which made him one of the most sought after animals in Europe and North America, but rather the pelt for its barbed, fibrous under hair which was pounded, mashed, stiffened, and rolled to make felting material for hats. Hats of all descriptions were produced from this highly valued hair. Coats of a light coloring were used to make day-time hats and those of a more luxurious dark brown produced the elegant hats of the evening. Many shapes and styles were created to satisfy the fashion demand, formal and informal styles and even some military headgear were made of beaver. From the 17th century through the mid-19th century, no European was without a beaver hat. Then the styles turned to other fabrics such as Oriental silk, and the beaver hat was locked away in the closet.

The beaver is an amphibious creature which averages four feet long from the tip of the nose to the end of the tail. Weighing about forty pounds, the beaver is the second largest rodent in the world. The tail, which is noted for its flat, rounded appearance, is ten to fifteen inches in length and covered with rough skin that resembles scales. The tail allows the beaver to steer in water and signal other beavers by slapping the water. The beaver is an excellent swimmer, and while under water can seal its ears, mouth, and nostrils. The beaver is generally light brown in color, although some may possess very dark coats. Their teeth are much longer and more powerful than those of most other animals and are used to fell trees which constitute the basis of their vegetarian diet, especially the bark of the birch, willow and cottonwood trees. Aspen trees are the favorite food of the beaver. The beaver uses its front feet to grasp trees and the webbed hind feet to swim. The beaver can cut trees down in a matter of minutes and is considered one of the finest engineers in the world in building dams. The beaver often emits a small quantity of castoreum (castor) upon the river bank, which will attract every beaver in the area. The odorous substance is used to “mark territory.” Trappers took advantage of this process and collected the castoreum left upon the banks, replacing the substance strategically above the traps. The beaver would be lured by the odor and then caught by the traps which lay beneath the surface of the water.

According to legend, the Indian tribes of early America respected and often worshipped the beaver. The Algonquin tribes along the St. Lawrence River believed that thunder was produced by their almighty beaver father, Quahbeet, as he slapped his giant tail against the ground. The five nations of the Iroquois confederacy were bound together by their common clans, such as the “beaver clan” in which members of the tribe were reincarnated as beavers. In this way, any beaver in the vicinity of the tribe could be a close friend or relative. Many tribes shared this belief, thereby they refused to hunt beaver near their homelands as they might be killing a loved one. The Flathead tribe thought that beavers were a race of man that had angered the Great Spirit and, as punishment, were sentenced to a life of hard labor. In time the Indians’ adherence to the legends, however, was treated more casually with the introduction of the white man’s materials. The tribes valued the beaver pelts only as winter clothing and as bed robes; therefore, they were quite willing to trade these pelts for the much coveted modern articles from the States.

TIMELINE

1743 - Verendryes brothers, first Europeans to enter Wyoming

1803 - Louisiana Purchase

1806 - John Colter first white American to enter Wyoming

1811 - Wilson Price Hunt’s party crosses Wyoming

1812 - Robert Stuart’s party returning from Oregon discovers South Pass

1823 - William Ashley’s fur trappers arrive in Wyoming led by Jedediah Smith

1824 - Ashley’s trappers cross South Pass westward and find good trapping on the Green River and its tributaries

1825 - First rendezvous held in Wyoming on Henry’s Fork of the Green River 1826 - First recorded visit to Yellowstone Park by trappers

1826 - Ashley sells out to Jed Smith, D. Sublette, W. Sublette

1830 - First wagons being drawn by mules cross Wyoming to rendezvous

1830 - Rocky Mountain Fur Company organized

1832 - Battle of Pierre’s Hole

1832 - Captain Bonneville takes first wagons over South Pass

1834 - Fort William built (later Fort John and finally Fort Laramie)

1840 - Last rendezvous held

1842 - Fort Bridger established

(cont. page 2)